Chapter 1: How Does Students' Prior Knowledge Affect their Learning?

As a part of our class reading, we will be posting weekly reviews for each chapter of the book How Learning Works; 7 Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching by Ambrose, Bridges, Lovett, DiPietro and Norman.

Chapter one explores the first research-based principal of the book, that students’ prior knowledge affects how well they learn new material. Examples are given of how two instructors thought they sufficiently reviewed and discussed prerequisite knowledge, but their review wasn’t sufficient enough to really identify the gaps in the students’ prior knowledge. The chapter goes on to identify types of gaps in knowledge and steps to take in order to bridge prior knowledge to the introduction of new material.

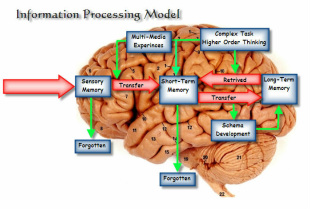

While students (and teachers) may believe there is solid prior knowledge, they may be lacking fundamental skills or actually possess misconceptions that will hinder moving to the next level of learning. The knowledge may be insufficient or inactive, and so the teacher must conduct some form of pre-assessment to best determine what needs to be reviewed. According to Ambrose, Bridges, Lovett, DiPietro and Norman, a solid understanding of prior knowledge is essential for new knowledge to be understood and retained (Ambrose, Bridges, Lovett, DiPietro, and Norman, 2010). It is essential to activate that prior knowledge before continuing on with new material.

Research suggests certain strategies teachers may use to identify types of misconceptions and gaps in knowledge, knowing it may take students some time to adjust to or fully grasp the bridge of knowledge. Those methods may include talking to colleagues who taught the student(s) previously, administering a pre-assessment, brainstorming to reveal prior knowledge, looking for patterns of error in student work, and more.

Methods used to activate accurate prior knowledge include the use of exercises, explicitly linking new material to knowledge from previous courses, using analogies and examples that connect to students’ everyday knowledge, etc. In some cases, there may be insufficient, inappropriate, or inaccurate prior knowledge. Bridging the gap may require minor review tactics or more drastic steps such as a departmental review of the prerequisite requirements for the course.

As a music educator, it is very common to conduct almost daily review of skills and knowledge. Each rehearsal usually begins with a daily warm-up that allows the students to focus on skills necessary to play the music that follows. This review can consist of technique, tone production, style of the period in which the piece was written, or discussion about the history relevant to the music and/or composer. All of this review is necessary to engage the students technically and to relate to the music emotionally. Although this review is a necessity for musicians’ good performance, teachers of academic subjects might consider daily academic review to be like a good “warm-up” for the lesson that follows.

REFERENCES

Ambrose, Susan A., Bridges, Michael W., DiPietro, Michele, Lovett, Marsha C., & Norman, Marie K. (2010). How learning works 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

Chapter one explores the first research-based principal of the book, that students’ prior knowledge affects how well they learn new material. Examples are given of how two instructors thought they sufficiently reviewed and discussed prerequisite knowledge, but their review wasn’t sufficient enough to really identify the gaps in the students’ prior knowledge. The chapter goes on to identify types of gaps in knowledge and steps to take in order to bridge prior knowledge to the introduction of new material.

While students (and teachers) may believe there is solid prior knowledge, they may be lacking fundamental skills or actually possess misconceptions that will hinder moving to the next level of learning. The knowledge may be insufficient or inactive, and so the teacher must conduct some form of pre-assessment to best determine what needs to be reviewed. According to Ambrose, Bridges, Lovett, DiPietro and Norman, a solid understanding of prior knowledge is essential for new knowledge to be understood and retained (Ambrose, Bridges, Lovett, DiPietro, and Norman, 2010). It is essential to activate that prior knowledge before continuing on with new material.

Research suggests certain strategies teachers may use to identify types of misconceptions and gaps in knowledge, knowing it may take students some time to adjust to or fully grasp the bridge of knowledge. Those methods may include talking to colleagues who taught the student(s) previously, administering a pre-assessment, brainstorming to reveal prior knowledge, looking for patterns of error in student work, and more.

Methods used to activate accurate prior knowledge include the use of exercises, explicitly linking new material to knowledge from previous courses, using analogies and examples that connect to students’ everyday knowledge, etc. In some cases, there may be insufficient, inappropriate, or inaccurate prior knowledge. Bridging the gap may require minor review tactics or more drastic steps such as a departmental review of the prerequisite requirements for the course.

As a music educator, it is very common to conduct almost daily review of skills and knowledge. Each rehearsal usually begins with a daily warm-up that allows the students to focus on skills necessary to play the music that follows. This review can consist of technique, tone production, style of the period in which the piece was written, or discussion about the history relevant to the music and/or composer. All of this review is necessary to engage the students technically and to relate to the music emotionally. Although this review is a necessity for musicians’ good performance, teachers of academic subjects might consider daily academic review to be like a good “warm-up” for the lesson that follows.

REFERENCES

Ambrose, Susan A., Bridges, Michael W., DiPietro, Michele, Lovett, Marsha C., & Norman, Marie K. (2010). How learning works 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass