Chapter 4: How do Students Develop Mastery?

From Novice to Master…

As we learn and develop mastery of a skill, our level of expertise grows and changes with our ability to know when and how to use that knowledge. In the book How Learning Works (Ambrose, Bridges, Lovett, DiPietro, and Norman, 2010), we learn that for novices to be pushed to the next level, we must present them with information and tasks that requires them to use the skills to the point of autonomy as well as figure out how to transfer what they have learned to new situations.

As we learn and develop mastery of a skill, our level of expertise grows and changes with our ability to know when and how to use that knowledge. In the book How Learning Works (Ambrose, Bridges, Lovett, DiPietro, and Norman, 2010), we learn that for novices to be pushed to the next level, we must present them with information and tasks that requires them to use the skills to the point of autonomy as well as figure out how to transfer what they have learned to new situations.

Stages in the Development of Mastery

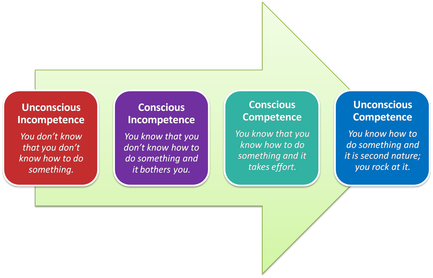

To understand the stages of development, we can observe the model created by Sprague and Stuart (2000). This model describes 4 levels of mastery using measurements of competence and consciousness. As novices, we are in a state of “Unconscious Incompetence”, where we don’t recognize what we need to know. As we gain knowledge and experience, we transition to “Conscious Incompetence,” where we are aware of what we do not know. Developing further, the third stage is “Conscious Competence,” where most of us remain. We have considerable ability and knowledge at our craft, yet it is not automatic; we must still think and act deliberately. The fourth and final stage is mastery, or “Unconscious Competence”.

At this level, our skills are so automatic that we are no longer aware of what we know or how we are doing it. “Experts” at this level apply and organize their knowledge very differently that at the other levels. Here, these individuals tend to mentally organize their information in “chunks” making it easier to recall more complex concepts more effectively. While this level of mastery is ideal in some situations, it can make for a less effective instructor. Because their actions are so autonomous, many “masters” are unable to effectively break down the processes effectively to novices.

As I was reading this section, I thought of instances where I was working with groups of advanced flute students. Occasionally we would be working on a trill in a classical-era piece of music. I would remind the students to mark their music to play the first note of the trill as an “appoggiatura”. Students who were currently working on classical music with their private instructor knew what I meant; others looked at me blankly. I assumed students at this level would be familiar enough with the word, but if they had only encountered appoggiaturas once or twice the knowledge was not quickly recalled. I need to remain more conscious of breaking down these steps and not assuming students are comfortable enough with these types of trills that they are automatic.

To understand the stages of development, we can observe the model created by Sprague and Stuart (2000). This model describes 4 levels of mastery using measurements of competence and consciousness. As novices, we are in a state of “Unconscious Incompetence”, where we don’t recognize what we need to know. As we gain knowledge and experience, we transition to “Conscious Incompetence,” where we are aware of what we do not know. Developing further, the third stage is “Conscious Competence,” where most of us remain. We have considerable ability and knowledge at our craft, yet it is not automatic; we must still think and act deliberately. The fourth and final stage is mastery, or “Unconscious Competence”.

At this level, our skills are so automatic that we are no longer aware of what we know or how we are doing it. “Experts” at this level apply and organize their knowledge very differently that at the other levels. Here, these individuals tend to mentally organize their information in “chunks” making it easier to recall more complex concepts more effectively. While this level of mastery is ideal in some situations, it can make for a less effective instructor. Because their actions are so autonomous, many “masters” are unable to effectively break down the processes effectively to novices.

As I was reading this section, I thought of instances where I was working with groups of advanced flute students. Occasionally we would be working on a trill in a classical-era piece of music. I would remind the students to mark their music to play the first note of the trill as an “appoggiatura”. Students who were currently working on classical music with their private instructor knew what I meant; others looked at me blankly. I assumed students at this level would be familiar enough with the word, but if they had only encountered appoggiaturas once or twice the knowledge was not quickly recalled. I need to remain more conscious of breaking down these steps and not assuming students are comfortable enough with these types of trills that they are automatic.

21st Century Practice Tools

When musicians think of "muscle memory" they usually think of the physical practice it takes to get fingerings, posture, breathing, etc. to become autonomous. But to get our "brain muscle" working to memorize terminology (important for properly interpreting the composer's intentions), flash cards still work well.

Google Gadgets offers a multitude of games and gizmos you can program to your specific needs. These gadgets' html code may be copied and pasted into your website. As an example, I have created and inserted below the Google Flash Card game. For additional skills reinforcement, you could even have your students create the gadgets themselves.

When musicians think of "muscle memory" they usually think of the physical practice it takes to get fingerings, posture, breathing, etc. to become autonomous. But to get our "brain muscle" working to memorize terminology (important for properly interpreting the composer's intentions), flash cards still work well.

Google Gadgets offers a multitude of games and gizmos you can program to your specific needs. These gadgets' html code may be copied and pasted into your website. As an example, I have created and inserted below the Google Flash Card game. For additional skills reinforcement, you could even have your students create the gadgets themselves.

Practice Makes Perfect

Reinforcing weak skills through targeted practice can be beneficial in most situations. Isolating a task through extended repetition commits that task to “muscle memory”; in music a scale is a good example of this. If the fingerings are automatic, the musician no longer needs to quickly think through what fingering comes next. Rather, they can turn their focus to the musical aspects of what they are playing. Once this step is accomplished, practicing a larger section of music that contains this mastered scale may be more effective, allowing the musician to focus on how the scale contributes to the overall musical statement.

Cognitive Load

We are all multi-taskers today. But performing multiple tasks at once can require more attention than we are capable of giving, resulting in mistakes and errors (Ambrose, Bridges, Lovett, DiPietro, and Norman, 2010). This can be improved by stepping back and focusing on just one skill. Once this skill is mastered, add another step, then another until the performance is improved. This is a technique very commonly used in music education. If we don’t take the time to master certain skills, they will never become automatic and will lead to bigger problems down the road. We usually tell students that it takes at least 21 times of playing something correctly for it to become habit. Master that skill, then continue to add a new skill one at a time.

Another term associated with cognitive load is “scaffolding”. Scaffolding is the point in which instructors assist students with some of the cognitive load which frees them up to focus on a smaller aspect of learning.

Reinforcing weak skills through targeted practice can be beneficial in most situations. Isolating a task through extended repetition commits that task to “muscle memory”; in music a scale is a good example of this. If the fingerings are automatic, the musician no longer needs to quickly think through what fingering comes next. Rather, they can turn their focus to the musical aspects of what they are playing. Once this step is accomplished, practicing a larger section of music that contains this mastered scale may be more effective, allowing the musician to focus on how the scale contributes to the overall musical statement.

Cognitive Load

We are all multi-taskers today. But performing multiple tasks at once can require more attention than we are capable of giving, resulting in mistakes and errors (Ambrose, Bridges, Lovett, DiPietro, and Norman, 2010). This can be improved by stepping back and focusing on just one skill. Once this skill is mastered, add another step, then another until the performance is improved. This is a technique very commonly used in music education. If we don’t take the time to master certain skills, they will never become automatic and will lead to bigger problems down the road. We usually tell students that it takes at least 21 times of playing something correctly for it to become habit. Master that skill, then continue to add a new skill one at a time.

Another term associated with cognitive load is “scaffolding”. Scaffolding is the point in which instructors assist students with some of the cognitive load which frees them up to focus on a smaller aspect of learning.

Transfer of Knowledge

Knowing how to transfer knowledge in one context to another is said to be “near” if the contexts are similar. If they contexts are different, they are said to be “far”. Without proper mastery of knowledge, students may fail to transfer knowledge properly. In my experience teaching music, “sight reading” (playing a piece you have never seen before, often a requirement for auditions) could be an example of far transfer of knowledge. Students are given a short time to review basic elements of the piece then are asked to perform it. In addition to playing correct notes and rhythms, judges are looking for many other musical aspects that should be automatic (a sign of skill mastery, when they do not need to be thought out, but rather occur intuitively).

Building Skills and Knowledge Transfer

Applying skills in “real life” situations can encourage knowledge transfer. This may be difficult in some classes, but instrumental music teachers at a local high school have thought of a way to encourage transfer that helps in two ways. Those who are taking band or orchestra for honors credit are required to teach at least one private student once a week. As the honors students are engaging with less advanced students, they must mentally put themselves in a beginner's place. Verbally and visually explaining finger position, how to breathe, how to produce a sound…while helping the beginner become a better performer it also reinforces the student teacher’s skill level as well. If the honors student has developed any bad habits themselves, they will be forced to address it as a mentor for their student.

In Conclusion…

In order to develop mastery, skills at various levels must be mastered. Weakness in any one level will result in gaps in knowledge that affect mastery. In order to become an effective teacher, these weaknesses must be overcome.

REFERENCES

Ambrose, Susan A., Bridges, Michael W., DiPietro, Michele, Lovett, Marsha C., & Norman, Marie K. (2010). How learning works 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Sprague, J., & Stuart, D. (2000). The speaker's handbook. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt College Publishers.

Knowing how to transfer knowledge in one context to another is said to be “near” if the contexts are similar. If they contexts are different, they are said to be “far”. Without proper mastery of knowledge, students may fail to transfer knowledge properly. In my experience teaching music, “sight reading” (playing a piece you have never seen before, often a requirement for auditions) could be an example of far transfer of knowledge. Students are given a short time to review basic elements of the piece then are asked to perform it. In addition to playing correct notes and rhythms, judges are looking for many other musical aspects that should be automatic (a sign of skill mastery, when they do not need to be thought out, but rather occur intuitively).

Building Skills and Knowledge Transfer

Applying skills in “real life” situations can encourage knowledge transfer. This may be difficult in some classes, but instrumental music teachers at a local high school have thought of a way to encourage transfer that helps in two ways. Those who are taking band or orchestra for honors credit are required to teach at least one private student once a week. As the honors students are engaging with less advanced students, they must mentally put themselves in a beginner's place. Verbally and visually explaining finger position, how to breathe, how to produce a sound…while helping the beginner become a better performer it also reinforces the student teacher’s skill level as well. If the honors student has developed any bad habits themselves, they will be forced to address it as a mentor for their student.

In Conclusion…

In order to develop mastery, skills at various levels must be mastered. Weakness in any one level will result in gaps in knowledge that affect mastery. In order to become an effective teacher, these weaknesses must be overcome.

REFERENCES

Ambrose, Susan A., Bridges, Michael W., DiPietro, Michele, Lovett, Marsha C., & Norman, Marie K. (2010). How learning works 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Sprague, J., & Stuart, D. (2000). The speaker's handbook. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt College Publishers.