Chapter 2: How Does the Way Students Organize Knowledge Affect Their Learning?

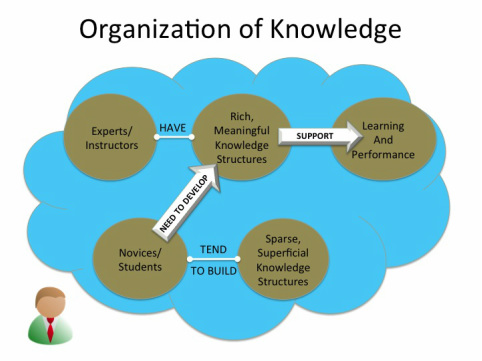

The subject of this chapter was to explore the differences between how novices and experts organize knowledge, and how this affects one’s learning. It also explores ways to help students organize material in a hierarchical method so their prior knowledge will help serve as a foundation for the new material.

The chapter begins with examples of two teachers describing how they introduce new material to their classes and how the students don’t seem to be able to relate the old and new knowledge in a deeper, more connected manner. The teachers seem to be teaching in one manner but expecting a different, broader connection to the materials on the tests, which is not happening.

The chapter continues to explore how the students may be organizing and processing information and how this determines the way in which they can apply it later. This is important because how we organize and retain information determines how we can relate it to new learning later (Ambrose, Bridges, Lovett, DiPietro, & Norman, 2010). Students who can recall and relate prior learning to new information are building more meaningful connections than those students who simply memorize lists or facts from a book. Through observations, it has been found that experts use knowledge to build structures and foundations that connect relativity of some information to another. Novices may memorize chunks of information but have not yet developed that connectivity of knowledge. Effective instruction can encourage the building of those connections.

Research has indicated that we organize information naturally as associations with other information, and it builds over time. An example was given using the way we in the United States use different labels for our relatives, versus how other countries such as China have different ways of categorizing relatives depending on the role they play in a person’s life or if they are maternal or paternal relatives (Ambrose, et al., 2010). We organize knowledge in the way we will best be able to use and recall it later. Because of this, when we are teaching new material we should practice in the same manner in which students will be expected to recall and relate it to other materials. The testing should also match the teaching method.

As researchers studied knowledge of novices and experts, it was discovered that the experts’ knowledge is much more densely connected. This is in large part due to the fact that they find ways to associate the chunks of information they have learned, such as other historical events that occurred at the same time, or just finding ways that one bit of information is relative to the others. Novices showed fewer nodes (represented as dots in the image to the left) and fewer links between them. Experts showed more interconnected knowledge structures, much like the image shown here. Difficulties in learning or recalling information occurs when links between the nodes are not connected. Research has shown that students learn more efficiently when they are provided with some type of organizational structure (Dean & Enemoh, 1983).

When I was an undergrad, I participated in a demonstration of how- by association- one could recall detailed information associated with every letter of the alphabet. This demonstration was done in a quiet classroom over a period of about 30 minutes. Because of the “association” factor linking something new to what we were already familiar with, it was surprisingly successful. Most of us remembered all the information for each alphabet letter. I retained that information for quite a long time. Validating this experience, the book goes on to state that students were more successful in learning when they were given “advance organizers”- a method of activating prior knowledge to associate it with new knowledge (Ausubel, 1960, 1978).

The book gives an example of experts’ ability to respond more quickly to relative information by an example of novice and experts’ chess mastery. It was found that experts could glance at a board and replicate the positions of the chess pieces exactly in a short amount of time. Novices took much longer and had many more errors. It was found that the experts were able to visualize the chessboard in chunks and notice relationships between the pieces more quickly and accurately. For them it was easier to memorize relative chunks of information rather than isolated information.

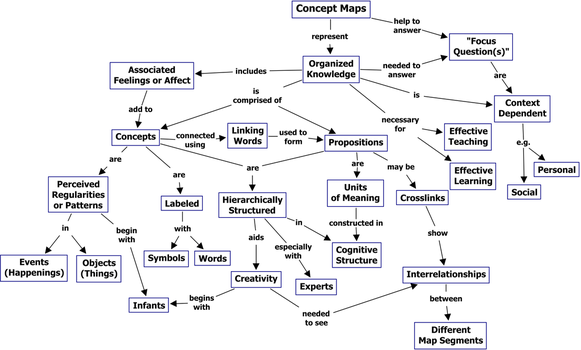

So, if students perform better when the organization of knowledge is matched to the task, how can teachers introduce new material in a meaningful way? "Concept mapping" is a way to provide students with an organized structure that will help create associations of prior knowledge and new information. Explaining to students the short- and long-term objectives for the class may also help them create associations of information. Pointing out associations to information they have previously learned is very helpful. As I am reading more of this book, I find so many correlations to an instrumental music curriculum. The nature of learning an instrument is to build upon prior knowledge; really, there is no way around it. In fact, it is almost impossible to achieve the next level of success if you have not mastered prior skills. There is an advantage in instrumental music classrooms in that the students usually have the same instructors, or a small staff who team-teaches, for many years and know the skill level and learning style of every individual student at the beginning of each school year. It reinforces to me how difficult it must be for a classroom teacher to assess every student in the same manner, and the time they must spend to bring every student “up to speed” to begin the year or a new unit.

I like how this chapter explains and outlines how to make those important connections to initiate higher-level learning; we can all incorporate the methods here as a good way to introduce new material and highlight deeper features of our lessons and as students ourselves.

REFERENCES

Ambrose, Susan A., Bridges, Michael W., DiPietro, Michele, Lovett, Marsha C., & Norman, Marie K. (2010). How learning works 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ausubel, D.P. (1960). The use of advance organizers in the learning and retention of meaningful verbal material. Journal of Educational Psychology, 51, 267-272.

Ausubel, D.P. (1978). In defense of advance organizers: A reply to the critics. Review of Educational Research, 48, 251-237.

Dean, R. S., & Enemoh, P.A. C. (1983). Pictorial organization in prose learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8, 20-27.

The chapter begins with examples of two teachers describing how they introduce new material to their classes and how the students don’t seem to be able to relate the old and new knowledge in a deeper, more connected manner. The teachers seem to be teaching in one manner but expecting a different, broader connection to the materials on the tests, which is not happening.

The chapter continues to explore how the students may be organizing and processing information and how this determines the way in which they can apply it later. This is important because how we organize and retain information determines how we can relate it to new learning later (Ambrose, Bridges, Lovett, DiPietro, & Norman, 2010). Students who can recall and relate prior learning to new information are building more meaningful connections than those students who simply memorize lists or facts from a book. Through observations, it has been found that experts use knowledge to build structures and foundations that connect relativity of some information to another. Novices may memorize chunks of information but have not yet developed that connectivity of knowledge. Effective instruction can encourage the building of those connections.

Research has indicated that we organize information naturally as associations with other information, and it builds over time. An example was given using the way we in the United States use different labels for our relatives, versus how other countries such as China have different ways of categorizing relatives depending on the role they play in a person’s life or if they are maternal or paternal relatives (Ambrose, et al., 2010). We organize knowledge in the way we will best be able to use and recall it later. Because of this, when we are teaching new material we should practice in the same manner in which students will be expected to recall and relate it to other materials. The testing should also match the teaching method.

As researchers studied knowledge of novices and experts, it was discovered that the experts’ knowledge is much more densely connected. This is in large part due to the fact that they find ways to associate the chunks of information they have learned, such as other historical events that occurred at the same time, or just finding ways that one bit of information is relative to the others. Novices showed fewer nodes (represented as dots in the image to the left) and fewer links between them. Experts showed more interconnected knowledge structures, much like the image shown here. Difficulties in learning or recalling information occurs when links between the nodes are not connected. Research has shown that students learn more efficiently when they are provided with some type of organizational structure (Dean & Enemoh, 1983).

When I was an undergrad, I participated in a demonstration of how- by association- one could recall detailed information associated with every letter of the alphabet. This demonstration was done in a quiet classroom over a period of about 30 minutes. Because of the “association” factor linking something new to what we were already familiar with, it was surprisingly successful. Most of us remembered all the information for each alphabet letter. I retained that information for quite a long time. Validating this experience, the book goes on to state that students were more successful in learning when they were given “advance organizers”- a method of activating prior knowledge to associate it with new knowledge (Ausubel, 1960, 1978).

The book gives an example of experts’ ability to respond more quickly to relative information by an example of novice and experts’ chess mastery. It was found that experts could glance at a board and replicate the positions of the chess pieces exactly in a short amount of time. Novices took much longer and had many more errors. It was found that the experts were able to visualize the chessboard in chunks and notice relationships between the pieces more quickly and accurately. For them it was easier to memorize relative chunks of information rather than isolated information.

So, if students perform better when the organization of knowledge is matched to the task, how can teachers introduce new material in a meaningful way? "Concept mapping" is a way to provide students with an organized structure that will help create associations of prior knowledge and new information. Explaining to students the short- and long-term objectives for the class may also help them create associations of information. Pointing out associations to information they have previously learned is very helpful. As I am reading more of this book, I find so many correlations to an instrumental music curriculum. The nature of learning an instrument is to build upon prior knowledge; really, there is no way around it. In fact, it is almost impossible to achieve the next level of success if you have not mastered prior skills. There is an advantage in instrumental music classrooms in that the students usually have the same instructors, or a small staff who team-teaches, for many years and know the skill level and learning style of every individual student at the beginning of each school year. It reinforces to me how difficult it must be for a classroom teacher to assess every student in the same manner, and the time they must spend to bring every student “up to speed” to begin the year or a new unit.

I like how this chapter explains and outlines how to make those important connections to initiate higher-level learning; we can all incorporate the methods here as a good way to introduce new material and highlight deeper features of our lessons and as students ourselves.

REFERENCES

Ambrose, Susan A., Bridges, Michael W., DiPietro, Michele, Lovett, Marsha C., & Norman, Marie K. (2010). How learning works 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ausubel, D.P. (1960). The use of advance organizers in the learning and retention of meaningful verbal material. Journal of Educational Psychology, 51, 267-272.

Ausubel, D.P. (1978). In defense of advance organizers: A reply to the critics. Review of Educational Research, 48, 251-237.

Dean, R. S., & Enemoh, P.A. C. (1983). Pictorial organization in prose learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8, 20-27.